By Ammar Ayad

Sbiba, Kasserine Governorate (Akher Khabar ) Oct 25, 2015 – The death of Issam al-Ramadani, 12, from viral hepatitis blamed on contaminated drinking water was a big shock to the people of Kasserine Governorate in general and to residents of Sbiba delegation in particular.

The child’s death earlier this year was an indication of an outbreak of Hepatitis and possibly other diseases in a city inhabited by some 6,000 people and close to one of the most important river tributaries in the central west region.

In many ways, the episode also reflects the failure of government projects launched in 2008 to supply drinking water to both the delegation and the governorate through the establishment of a water treatment plant between the delegation of Sbiba and the neighboring delegation of Jedelienne. The project, approved since 2011, is funded by the French Development Agency for 2.7 million Tunisian dinars ($1.588 million). The majority of homes are not connected to the governmental water grid.

A 2010 study conducted by Dr. Lutfi Mraihi, a pulmonologist, showed the prevalence of hepatitis among the residents of Sbiba to be as high as 40 percent, compared to the national average of 0.5 percent.

The most dominant type, according to the study, is Hepatitis C. But the study indicates 90 percent of these cases are treatable.

The residents of Sbiba suffer from chronic water shortages, despite the fact that the town is located in the heart of the Wadi al-Hatab, one of the most important wadis in central Tunisia and a main tributary of Wadi Zroud. The water flow in the wadi during the flood season in winter could reach up to 2,400 cm3 per second.

The water shortage has forced the residents to dig wells haphazardly or resort to other sources of water that are usually non-potable.

The usage of non-potable water that has caused diseases in the area is not limited to drinking and household consumption, in violation of the regional administration laws that ban the use of well-water for drinking, cooking, or food processing. The laws also place stringent conditions on the use of well water in bathing, swimming pools, and irrigation.

Violations have also occurred with regard to the agricultural irrigation regulations mentioned in the Water Gazette published in 1975 and amended in 1987, 1988, and 2001. The regulations requires water fit for consumption not to contain any hazardous or chemical substances, or bacteria and organisms harmful to health. In addition, water has to be free of contamination signs, and has to have acceptable characteristics in terms of its organic composition.

In addition, water fit for consumption must satisfy certain specifications and requirements, which are monitored through routine analyses conducted in laboratories approved by the Ministry of Public Health. Consumption includes consumption by cattle and irrigation of fruit trees, including apple and peach trees that the region is known for.

Developmental failure

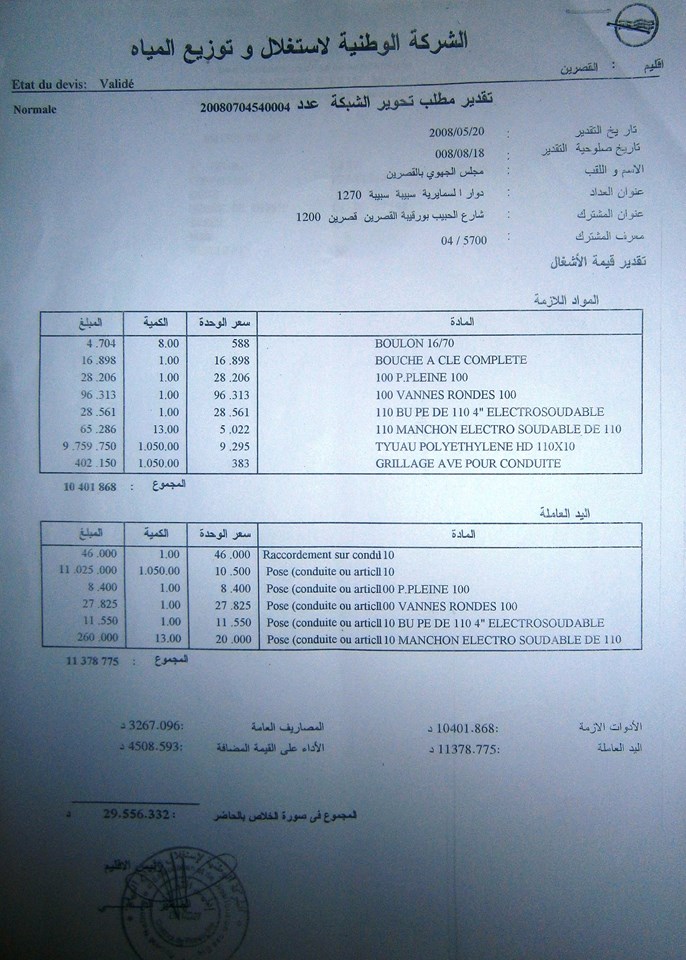

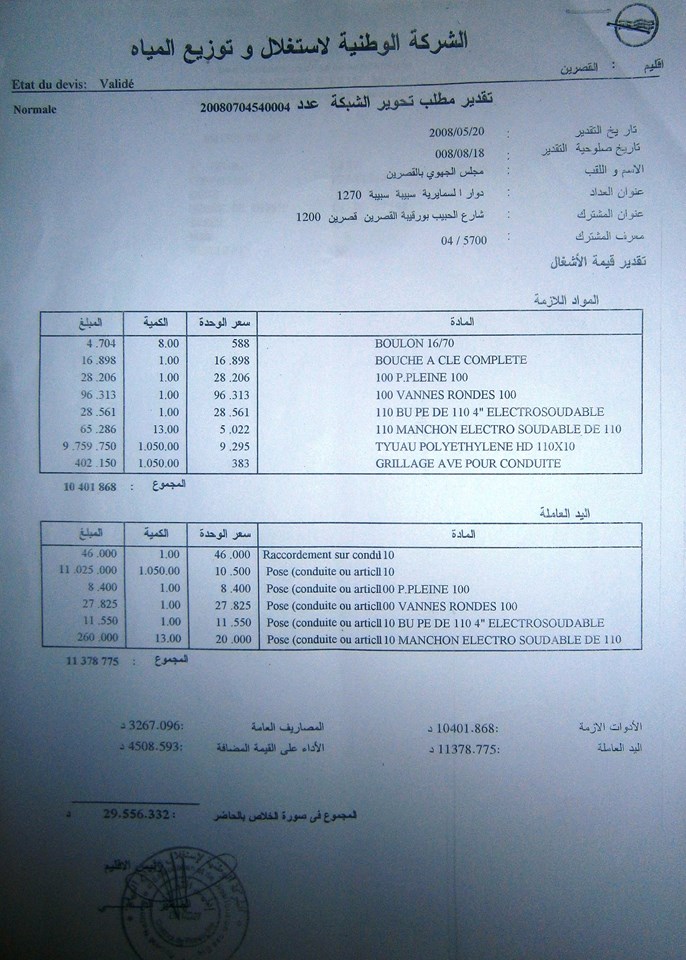

In 2008, the state allocated about 5.027 million Tunisian dinars ($2.645 million) to the Sbiba delegation out of 46.28 million dinars ($23 million) allocated to the Kasserine Governorate for water treatment projects.

In 2008, the state allocated about 5.027 million Tunisian dinars ($2.645 million) to the Sbiba delegation out of 46.28 million dinars ($23 million) allocated to the Kasserine Governorate for water treatment projects.

But until the publication of this investigation, none of the planned projects have been launched for several reasons including the lack of excavators and the absence of proper administrative project planning, according to documents obtained from the Sbiba delegation. In the meantime, local authorities continue to blame one another.

Wadi al-Hatab: The valley of death

Thanks to years of official neglect, Wadi al-Hatab became a dumping ground for waste from olive oil production (black liquor) and residents’ sewage to solid waste such as plastic bottles and cans thrown from local businesses. The environmental condition of Wadi Sbiba thus deteriorated, until its water springs became unfit for both for drinking and cattle according to the regulations of the Ministry of Agriculture and the Department of Public Health.

“I know that the water table is contaminated because the wadi is located adjacent to the public irrigation zone, but we have no choice other than use its water for our animals and plants,” said Hadi al-Klichi, senior p ublic health official.

ublic health official.

Farmers in Sbiba, who work in this irrigation zone which contains peach and apple trees on both sides of the wadi, told this reporter that they use the contaminated water from the valley often to water their trees, in the absence of a regularly monitored water source fit for irrigation.

It is worth noting that the Ministry of Agriculture bars farmers from watering their crops with sewage water, according to Order No. 1047 of 1989 (28 July 1989), violation of which is punishable by imprisonment.

Using contaminated water from Wadi al-Hatab, according to officials from the Ministry of Agriculture, poses hazards for the residents’ health and also risks contaminating the soil, which in the long run could become unfit for agriculture.

An official at the National Union for Agriculture and Fishing (independent organization) told this reporter: “Sewage water contains bacteria, heavy metals, and pathogenic organic compounds, posing a health hazard to farmers and consumers of irrigated crops.”

Well and mountain water

The lack of treatment of Wadi al-Hatab water forced residents of Sbiba to look for other sources for potable water. One temporary solution has been to dig water wells, which is what Youssef al-Ramadani, father of the deceased child Issam, did. Youssef bought an excavator but did not hire specialists.

Ramadani is one of many similar cases ones among Sbiba’s residents, who have sought to get their water from deep wells and neglected springs in the mountains, where there is little monitoring of the water resources. The result: deaths and hepatitis as well as kidney diseases.

The grieving father, looking up to the sky as if in prayer, says: “Who do you want me to complain to? I have only God to complain to, no one else listens.”

Ramadani’s home is only 150 meters away from Wadi al-Hatab, or the valley of death as the locals now call it.

He and his four sons, like many of the residents, suffer from kidney diseases caused by drinking contaminated waters, according to laboratory analysis carried out at the behest of this reporter.

The father cries as he remembers the death of his son Issam, who studied at the Uqba bin Nafie school in Sbiba, and had to walk 3.5 km each day to get there from home.

Issam became suddenly ill. His face and body turned yellow, and he started to vomit yellow bile. The parents took him to the local hospital, where he spent one night. Doctors at the hospital asked his parents to take him back home without clarification or a proper diagnosis. Two two days later, Issam died.

After Issam died, on April 7, 2014, there were repeated cases of Hepatitis in the town. The residents soon protested, demanding their right to safe drinking water. But the authorities have yet to respond in a serious way.

The issue of safe drinking water is haunting the residents, many of whom prefer to remain thirsty or walk tens of kilometers to get their water than to consume contaminated water from the tributaries of Wadi al-Hatab. However, many people have no choice but to consume any water they can find, whatever its source.

A woman in her 70s from the Wadi al-Sbitat region told us she has to walk more than 5 km every day to fill a plastic gallon she carries with water, sometimes twice a day.

Another resident told us: “We know the water is dirty. I even have a kidney disease. What do you want me to do?”

The residents’ drinking water sources

With the impossibility of treating water or managing the resources of the valley that cuts through their town, the residents of Sbiba have three main sources for their drinking water.

The first source are the – untreated – springs in nearby mountains, now the preferred choice for poor families. The water there is turbid, and animals are known to drink and defecate in these springs whose water is used by women from the area for drinking and cleaning.

This reporter took samples from the spring known as El-Hfara in the mountain and had it analyzed in the Regional Public Health Administration laboratories in Gabès. The results revealed that the water was contaminated and unfit for human consumption, due to the presence of very high concentrations of fecal coliforms.

Tunisia’s drinking water specifications mean that the presence of fecal coliforms in water makes it unfit for drinking. This is in line with the guidelines of the World Health Organization (WHO, 2000) and the United States Agency for Environmental Protection (US EPA, 2001).

According to water and environmental experts, these bacteria cause diseases including hepatitis, cholera, and various kidney diseases that could become chronic and life-threatening.

The second option is haphazardly digging deep and shallow water wells, but only the well-off residents can afford that. According to the mayor of Sbiba, Saleh Barhoumi, there are 380 deep wells and 220 shallow wells, most of them dug at random.

The Ministry of Agriculture only monitors four wells, because they are classed under Code 63130, and are owned by citizens. However, it does not monitor any of the wells dug randomly alongside Wadi Sbiba, especially after the chaos that followed the 2011 revolution.

The Health and Environmental Authorities in the province say they monitor and analyses water resources based on requests from the owners of the wells. But many are reluctant to request this given the cost of the analyses, which range between $24 and $248 in a country where the average per capita income a year stands at $362.5.

These wells overlap with the sewage-contaminated water table. The Ministry of Agriculture is unable to monitor the digging of random wells given the difficulty to establish ownership of farmland. In addition, administration and monitoring capabilities are weak to begin with, according to Habib Mabrouk, official at the Regional Agriculture Administration.

This reporter took a sample from a hand-dug well at a field belonging to Youssef Ramadani, Issam’s father, for analysis. The water is used for many purposes, including drinking, irrigation, household consumption, and for cattle. It is not protected, covered, treated, or monitored.

The results showed that the well water is unfit for human consumption because it contains high levels of fecal coliforms in violation with international standards.

Well expert Mohamad Daghesni stressed that digging wells requires special techniques, after analyzing the layers to be dug, their hardness, and the water table to avoid any contamination to the water table.

“The residents rarely come to us to dig wells in accordance with health and legal specifications, perhaps because of the high cost,” Daghesni adds. The cost of one well varies according to depth, the nature of the soil, and the drilling technique used. The cost could reach up to $4,000 for mechanical drilling and a maximum $1,000 for manual drilling.

The third source of drinking water, especially for people in remote regions, are private water tankers. The owners fill them up from a reservoir in the Sbitat region, belonging to the Tunisian Water Company, and then sell the water for $15 per tank-load. The water is then pumped through a run-down pipe into a reservoir located between the homes of the locals where the water is stored.

The number of tanks is small: five for every 600 residents. This has often prompted residents to compete to buy water from the tankers, regardless of the quality of water.

The tankers are owned by private citizens who make a living from selling and distributing water, which they obtain from the publicly owned Tunisian Water Company supervised by the Rural Engineering Administration. The Health Protection Authority is in charge of monitoring these tankers. In 2013, 12 violations were recorded – 2 per tanker – but the monitoring process is not rigorous enough. Moreover, the owners of these tankers often ignore the recommendations of the Health Protection Authority, which are usually of a punitive nature.

The author examined the water storage tanks in a number of homes, a primary school, and a local clinic.

The water stored in these reservoirs remains stagnant between 15 days and 3 months, according to Hadi Klichi, the Regional Health Authority official. This reporter visited him in his home and took a water sample for testing from the reservoir where he stores water.

There was significant moss growth on both sides of Klichi’s reservoir. When we asked him how a health official like him could be drinking contaminated water, he quickly answered: “If we do not drink it we would die of thirst.”

Meanwhile, an official from the Tunisian Water Company said the company is only responsible for its own tanks.

However, this contradicts a government report issued by the General Audit Bureau 2012 (p.361), which said even monitoring of the company’s tanks was lacking adequate follow-up. The report stated: “The Tunisian specifications do not have a mandatory nature, and it has not been established what the maximum limit is for a number of toxic substances included in this specification” related to the company’s water resources.

Monitoring by the same department also established that the tests carried out by the company do not include the water exported and distributed. It established that there was a lack of regular sample taking in accordance to Tunisian specifications, while the company’s monitoring of the physiochemical composition of the water did not include all substances listed in the specification.

An official at the Tunisian Water Company admitted that only 4.65 percent of Sbiba is directly linked to the rural potable water grid.

The company distributes water to citizens in two ways: direct connection or through coordination with Regional Engineering Departments to bring water to unconnected regions, by establishing reservoirs directly supervised by Regional Engineering. In turn, officials at the Regional Engineering sell water to tankers, which then sell water to residents.

The official said that the company is working to increase the water supply to the regions in the near future, citing tenders launched by the company in the past two years. However, the delay is due to requests for amendments by official bodies to the paths planned for the potable water connections, as he said.

Dying along the way

Although water is available in Sbiba, neglect is rife. Despite promises to implement projects that have already been planned, these have not seen the light, according to civil society activist Suleiman Sayari.

Sayari says kidney diseases and hepatitis are prevalent in the area. This conclusion is supported by Hadi Klichi, who says that the delegation of Sbiba has become a hotbed for all types of hepatitis.

A number of residents told us they have to undergo dialysis in the local hospital in Sbiba, while others needed operations to remove stones using laser surgery.

The difficulty of obtaining official figures

The author went to a clinic in the delegation of El Kantra in the same governorate. The official there declined to provide any figures on medical conditions in the region caused by water contamination.

In a written request, the reporter asked the local hospital in Sbiba to give him figures on cases of hepatitis and kidney disease. But the request was neglected. All officials refused to speak, and the reporter was even threatened with calling the police.

Qais ben Ahmad, who is in charge of the SOS – Hépatites Tunisie Association, the only hepatitis awareness group in the country established in September 2012, says he has tried in vain to obtain accurate figures on the disease.

In contrast to the blackout imposed on the number of infected people in Sbiba and Kasserine in general, the Minister of Health Said Aidi has raised the alarm on the outbreak of hepatitis in the Tunisian interior, without naming which regions. In a press conference in May, he called for a national survey of hepatitis cases. He ordered measures to be taken to offer hepatitis vaccinations and treatment free of charge, especially to people with special needs.

Symptoms of hepatitis appeared in schools in Sbiba and the province of Kasserine in general, according to medical sources. The sources said that an inspection of schools in the governorate in 2013 found 300 hepatitis cases among children and 13 among teachers. The Ministry of Health refused to comment on these figures, despite repeated attempts.

In the absence of official figures, this reporter approached Sharaf al-Din Bakari, pulmonologist and one of six doctors in Kasserine who specialize in hepatitis. Bakari said hepatitis C cases are in the hundreds, but had no specific figure.

For his part, Dr. Mraihi said consuming contaminated water is one of the causes of hepatitis, and stressed that failing to treat it would lead it to evolve into other types.

In turn, Dr. Mohamad Nasser Moussa, a nephrologists in the Kasserine Provincial Hospital, said that kidney diseases are “highly prevalent” in the governorate, especially in the cities of Thala and Sbiba as a result of consuming water high in calcium, oxalates, and uric acid. The rest of the doctors refrained from giving any information on the issue.

Sbiba symbol of the water crisis

“The right to water is guaranteed”, according to Chapter 44 of the post-revolutionary constitution. However, the state of affairs in Sbiba and surrounding villages is an example of the distance between text and reality.

Are there solutions?

The regional director of the Water Treatment Department at the Kasserine governorate Naji al-Badri says the project for a treatment plant in Sbiba and neighboring villages is experiencing some difficulties related to real estate. He said his department is working hard to overcome these problems.

The project needs 5 hectares of common land to be allocated by the Development Councils of Sbiba and Jedelienne.

The head of Sbiba delegation Huthama ben Harrath said: “The real-estate issue has been resolved since last May.” The inspection was signed by the director of state properties, who prepared a report that was submitted to the director general of assessments to determine its value under document No. 506 dates 20/5/2015, said Harrath.

Atef Boughattas, the former governor, corroborated the results documented by this investigation, saying: “There is a real environmental disaster in Wadi Sbitat in Sbiba.”

He added: “We are convinced of the need to establish a treatment plant in the area as soon as possible. The project is under study and the allocations are ready. But there is a real-estate problem that will be addressed soon.”

The discrepancies between the accounts of the officials regarding the contaminated water of Sbiba have raised doubts among the residents on the seriousness of officials in saving the areas and the lives of its residents from this scourge.

Until the promises of the governor and officials are delivered, the people of Sbiba will continue to wonder why their village has been neglected since independence. The daily suffering and the water-borne diseases will continue amid the absence of real development programs in the township of Sbiba and its environs, and the mismanagement of public funds.

This investigation was completed with the support of Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism (ARIJ) — www.arij.net – and coached by Hadi Yahmad.

ublic health official.

ublic health official.

Leave a Reply