7iber – The Sharia court in South Amman buzzes with clients on a hot summer day. Squeaky doors and clacking heels mix with whispers of a crowd of men and women waiting in the main hallway to be served by the court staff. Sara’s young face stands out among the crowd and so does the reason that brought her to court. She came for Katib Kitab – signing marriage contract – to her 23-year-old fiancé a day after she turned 15. Sarah recounts with sorrow how the judge only asked her one question during the 10-minute encounter: Do you want to marry him or were forced by anybody?” “I want to,” Sarah answered.

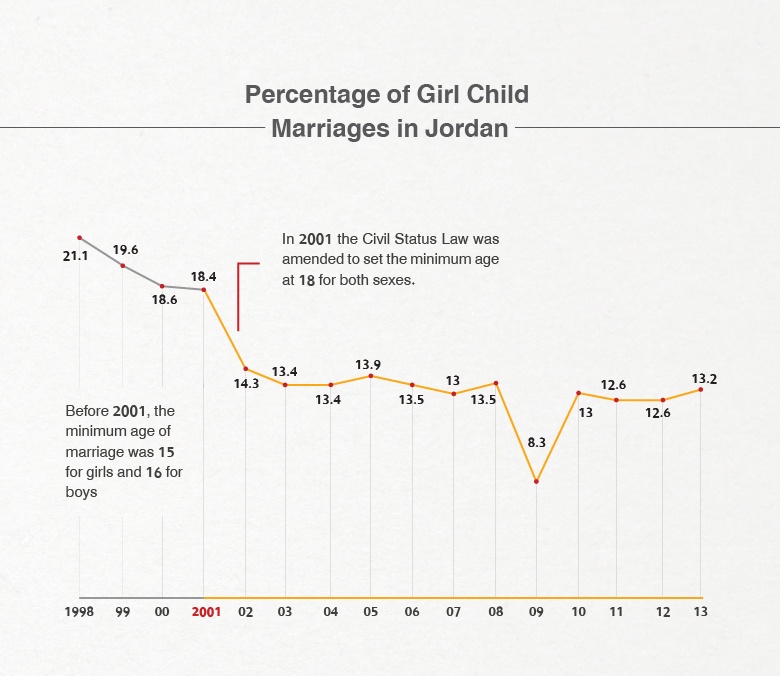

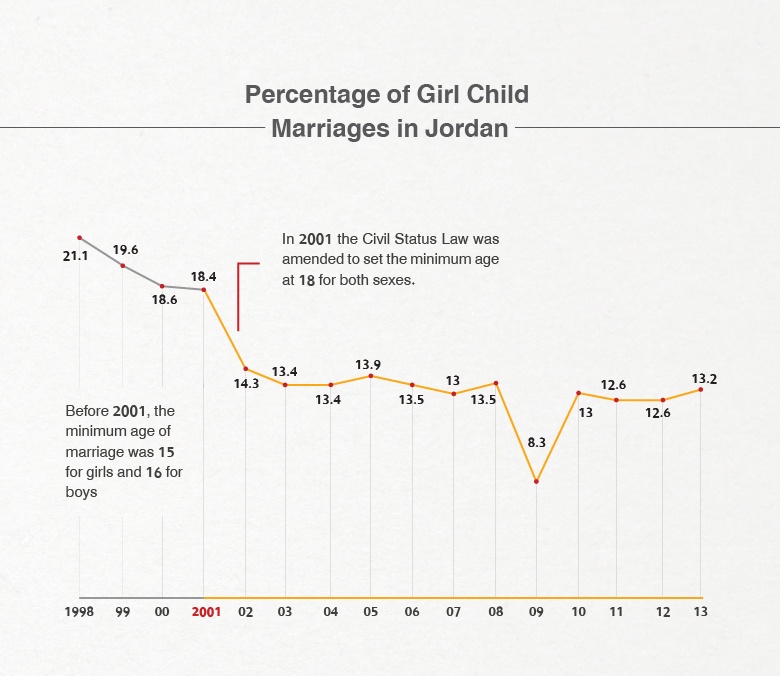

The marriage contract was sealed afterwards. Unfortunately, this is not a unique scene in Jordan’s Sharia courts where on average 8,000 to 10,000 underage girls are wed every year; almost 13 per cent of overall marriages taking place in the country. (See graph below) The minimum age of marriage in Jordan used to be 15 for girls and 16 for boys until 2001 when the Civil Status Law was amended to set the minimum age at 18 for both sexes. The amended law, however, states that “the judge may in special cases approve marriages of those who are 15 years old and above if the marriage has any benefit determined by regulations outlined by the head of the Chief Islamic Justice Department (CIJD)”.

This investigative report reveals that the amendments to the Civil Status Law have failed to protect children from marriage. The loophole in the law, which gives judges the sole authority to approve marriages of children amidst lack of supervision from authorities, has turned the “exception” into a rule. As a result, thousands of girls fall victim to the practice of child marriage every year, which violates their human rights by stripping them of their childhood and interrupting their education. Slow Decline An examination of official figures from 1998 until 2013 shows that despite the amendment which took place in 2000, the decline in girl child marriages was only 4-6 %. Moreover, there was almost no decline over the past decade as figures kept the same percentage of 13 per cent of overall marriages. The CIJD said it can only provide age figures until 2000. Therefore, this reporter used figures by Jordan Civil Status Department, obtained via UNICEF Jordan’s office.

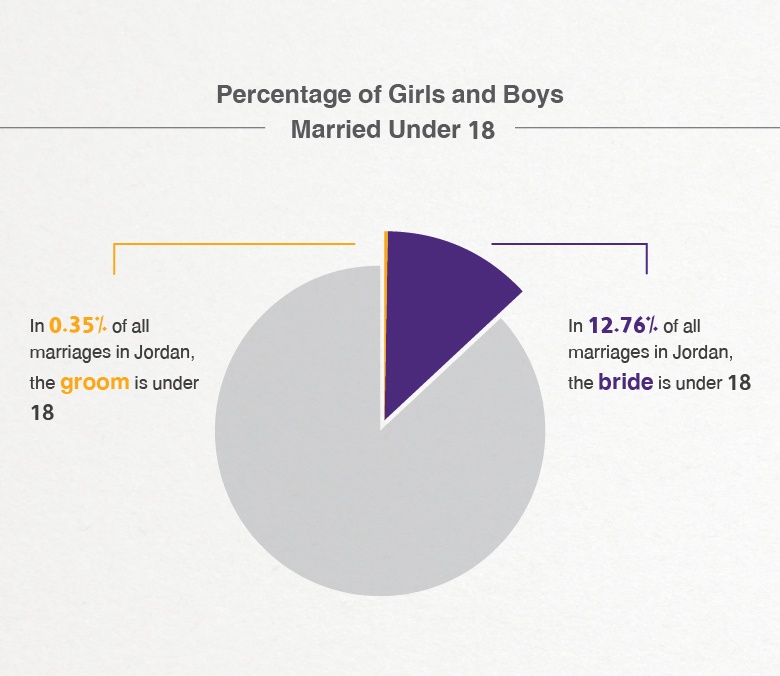

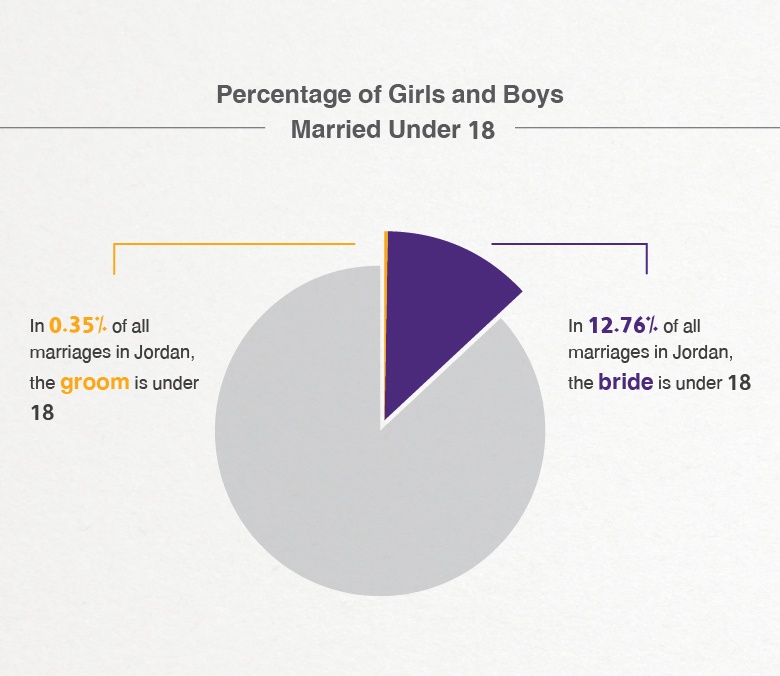

Although both boys and girls are at risk of underage marriages, it is mainly girl children who are subjected to the practice. A review of CIJD’s reports from 2003 to 2013 indicates that 79,686 girls (almost 12.8 per cent of the overall marriages) were married below the age of 18 as opposed to only 2,429 boys (almost 0.36 per cent of the overall marriages) out of 695,187 marriages registered during the past decade.

How underage marriages happen For this investigation, the reporter examined official statistics and conducted in-depth interviews with 30 child brides, all of whom got married during the past three years in six governorates across Jordan. She also interviewed social workers and human rights activists. The reporter only interviewed Jordanians and Palestinian refugees whose marriages are registered in courts. Underage marriages in the Syrian refugee community in Jordan have been extensively covered in regional and international media. She requested an interview with the head of the Chief Islamic Justice Department (CIJD). But instead, she was directed to their media officer, Mansur Tawalbeh. The reporter filed a list of questions in writing, but CIJD did not respond to any question. They gave the reporter a copy of CIJD’s regulations for judges to approve marriages below the age of 18 — a document already available online. The CIJD’s office denied the reporter access to Sharia Courts to interview judges and observe the process of approving underage marriage, saying that “it violates people’s privacy”. Court sessions are public in Jordan including those pertaining to divorce and marriage. According to the CIJD’s regulations, published in the official gazette no. 5076 in 2011, to approve marriage below the age of 18 the judge must:

– Ensure the complete will and approval [of spouses].

– Validate the “necessity” in the marriage, whether “economic, social, or security” which could “provide benefit or ward off corruptness”.

The regulations also stipulate that courts must take into consideration “as much as possible” there being an obvious benefit in marriage “such as ensuring that the age difference is reasonable, that it’s not a second marriage, and that the marriage does not interrupt their education.” On the other hand, child brides and their families say that the process of approval of their marriages was much easier than regulations state. When they were asked to make a list of the questions asked by the judge to assess the “benefit” from their marriage, there was one question only: “Did you want to marry him or were you forced by someone?” The reporter, however, came across two cases of underage marriages which the judge rejected. But then the parents succeeded in getting approval from another judge at a different court. On paper, the marriage contracts of child brides look exactly the same as adults. It does not state anywhere the reasons why the judge approved the marriage.

CIJD says their judges document the reasons for approving the marriage, but they denied the reporter access to those documents. Jordan in breach of human rights’ conventions Although setting the minimum age of marriage at 18 was considered an achievement for Jordan, the state “is failing to meet its international human rights obligations to protect thousands of girls from child marriage,” says Rothna Begum, a London-based Researcher on Women’s Rights in the Middle East of Human Rights Watch. Jordan is a state party to the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and the Convention on the Rights of Women (CEDAW) since 1991 and 1997 respectively. These child marriages are not only in breach of international conventions, but also violate national legislation. In Jordan, 18 is the standard minimum age required to obtain a driver’s license, join a political party, vote for parliamentary and municipal elections, press charges against someone, open a bank account and be in charge of one’s own finances. “If the law questions their ability to vote for a parliament member or to drive a car below the age of 18, how could anyone expect them to head families and raise children at that age?,” asked Hala Ahed, lawyer and human rights activist of the Jordanian Women’s Union (JWU).

Long-standing tradition or quick fix? Although child marriage has roots in the Arab culture, which values Sutrah (protection) for girls, tradition is no longer the main reason behind the high prevalence of these marriages in Jordan.

This reporter documented that marriages of young girls have become an answer to financial hardships, family problems, and potential “social scandals”. Only one of the child brides interviewed for this story said that her marriage was part of a long-standing family tradition. The vast majority said that their marriage came as answer to their families’ financial problems.

Being the fourth child of eight girls, Israa knew that her father –who earns a monthly income of $250 from occasional work in lifting and construction– could never send her to school, and that she could not call the two-bedroom flat in the crowded neighbourhood of Nuzha home for the rest of her life. “My parents always said they were relieved each time one of us was married,” said Israa, who was wed to a pharmacist with a “decent” income. A recent study by UNICEF Jordan cited poverty as a major cause for child marriages among Jordanians, especially “when there are too many daughters at home.” In some extreme cases like that of Sameera, the marriage came as a bargain between the parents and the groom who paid a high dowry. “Once, I ran to my parents’ home barefoot. My father did not care to hear what happened. He returned me back to my ex-husband’s home in exchange of JD100 ($140),” said the 18-year-old who was wed to a family friend in exchange of JD 5,000 ($7,000) dowry.

Such cases amount to “human trafficking and the parents must be held accountable for it,” said Taghreed Hikmat, Human Rights activists and head of Jordan’s National Association against Human Trafficking. Stolen Childhood Flipping through the remaining wedding photos, Sara speaks of her seven-month marriage that stripped her of her childhood. In one of the photos, Sara appeared wearing a puffed dress and heavy-make up. “On that day, my mother told me you are becoming a woman now and you must make us proud by being a good wife and good daughter in law,” said Sara. But the bride did not realize what a difficult path she was going to take after the party ended. “I was expected to cook very well, clean the house, and look after my husband’s younger siblings.” Sara and other child brides said during interviews that they had to share accommodation with their in-laws. Being under the scrutiny of the in-laws, child brides reported limited freedom to communicate with their families and old friends, let alone make new ones.

The Demographic Health Survey (DHS), published by the Department of Public Statistics in 2012, said only 40 percent of married women aged (15-19) were able to make “some decisions” regarding buying personal items, personal health, and visiting family and friends. Interrupted education For that puffed wedding dress, Sara gave away so many things she cherished, including her dream to become an Arabic language teacher. “He had preconditioned that I quit school,” she said. Most girls interviewed dropped out of school immediately after marriage or the engagement party.

According to figures by the Ministry of Education, the percentage of girls dropping out of school increases in the secondary stage and continues after the 10th grade, keeping the percentage at %0.52 for girls and %0.31 for boys. The Ministry cited “early marriage” as a reason for girls dropping out of school, but did not give further clarifications. Although education is mandatory until the tenth grade, none of the girls interviewed said their parents were questioned by the authorities for pulling them out of school. The ministry did not respond to the reporter’s repetitive attempts for an interview. Child mothers Just one month after her marriage, Sara says she was interrogated by her mother in-law to check if she was pregnant. When the answer appeared to be “No”, Sara was taken to three gynaecologists to check for the cause. “The doctor said my womb is as clear as gold, but my body is yet to grow,” Sara said. She attributes the ongoing clashes with her in-laws to the fact that she had a miscarriage later.

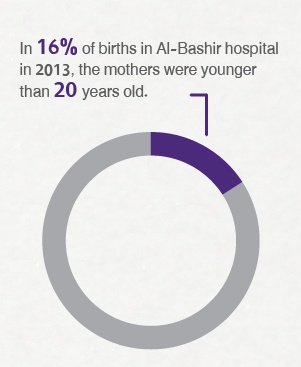

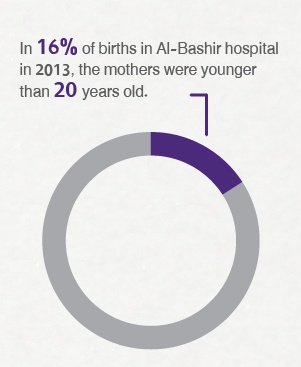

All child brides interviewed said they were expected to have children immediately after marriage. Twenty eight of them had children before the age of 18 and five of them reported having a miscarriage. There is no research or information available about teenage mothers in Jordan.The reporter obtained statistics from al-Bashir hospital, one of the largest state-run hospitals in the country. The data revealed that of 10,811 cases of birth in 2013, around 1726 cases involved mothers below the age of 20. These figures reveal cases of mothers holding Jordanian identification numbers and exclude Syrian or Iraqi women refugees. “Puberty in the region is defined between 11 and 13 years of age,” said Abul-Manee Sulieman, a gynaecologist at al-Bashir hospital. “Pregnancies and labor before girls are fully grown could have severe consequences on their health.” High risk of violence The most difficult aspect of the research was addressing the question of violence against girls by their partners or their in-laws. Those whose marriages ended in divorce were more open to talk. High expectations of girls to behave like adults often triggered violence against them, activists and social workers say. “By abusing these girls, verbally, emotionally or physically, adults think they are actually disciplining them to modify their behaviour,” lawyer Hala Ahed of JWU said. Sara said that her ex-husband always promised to discipline her and that he once hit her with a belt for ten minutes for refusing to wash the stairs. Their young age and limited knowledge of their rights put underage brides at higher risk of violence in comparison with adult wives. “They are too young to know their rights or even distinguish between what is wrong or right ,” said Zain Abbadi, head of Dar Al-Wifaq, a state-run shelter.

More than 25 percent of the women who stay at the shelter were married below the age of 18, Abbadi said. According to the 2012 Demographic Health Survey, 12.5 per cent of married girls aged (15-19) said they experienced physical violence by their partners, 7.9 per cent experienced sexual violence during pregnancy, and 84.1 per cent said it was “acceptable for a husband to slap or beat his wife given there is a good reason for it.” Civil society divided Civil society groups and activists voice concerns over the prevalence of child marriage and the improper implementation of the exceptions in the law. However, there is not one single national campaign targeting lawmakers and judges. A few dispersed awareness activities are happening across the country, but mainly targeting Syrian refugees and not Jordanians. Activists also remain divided on whether exceptions in the law should be allowed or removed. In Jordan, a conservative Muslim and tribal society, marriage is a rite of passage and premarital sex is a taboo. “If the girl is in love with a man, and she is in a sexual relationship, which could lead to pregnancy, marriage would be the answer,” said Inaam Asha of Sisterhood Is Global Institute/Jordan (SIGI/J). Others are not so convinced. “The government and civil society groups are responsible for providing awareness and social protection,” said Hala Ahed of the Jordanian Women Union. “Exceptions should only be granted in rare cases by a committee of judges and under the supervision of civil rights groups,” said Lubna Dawany, lawyer and president of SIGI/J. Uncertain Future As the debate between activists, lawmakers and implementers continues, thousands of girls in Jordan fall victims to the practice every year. The marriages of five of the interviewees ended in divorce including two girls who were married and divorced during the time of this investigation. Many said they would seek divorce if they had the family support for it. Undeterred by the stigma associated with divorced women, Sarah returned to school to fulfil her dream to work as an Arabic teacher one day. “My life was turned upside down in a few minutes,” she said. “So, why shall I worry that I am one year behind after my mates?”

This investigation was completed with support from Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism (ARIJ) – www.arij.net – and coached by Saad Hattar.

Leave a Reply